Egypt’s ideal environment — the legendary Nile and its eternal sunshine — have brought visitors to Egypt since Graeco-Roman times, but tourism as an industry was only born when Thomas Cook began to organise cruises and package tours to Egypt some 130 years ago.

It was a different world then. The year 1869 was crucial for Egypt, being the year that the Suez Canal was inaugurated — a momentous event not only for trade but also for tourism. With a sea route to the Orient opened up, this was an opportunity to tap a new potential market and the first escorted Thomas Cook “Nile cruise” was a resounding success. The Reverend Newman Hall was one of the passengers; he became one of the company’s most loyal propagandists. He wrote articles that were published in New York, which Cook reproduced in his magazines, Excursionist and Tourist Advertiser.

Cook was suddenly inundated with requests for trips to Egypt and the Holy Land. What was he to do? The interest was there, the potential was huge; Cook could do naught but respond. In 1870 his son, John Mason Cook, opened an office in the grounds of Shepheard’s Hotel in Cairo. Business was launched, and it soon flourished.

Tourists to Luxor and other sites made their bookings at the first Thomas Cook Office in Shepheard’s Hotel

How could it not? Anyone who could afford it wanted to escape the cruel European winters and Egypt offered the Nile, a dry climate and a wealth of ancient monuments — an irresistible combination. The weather was a particular attraction, since the dry climate was supposed to be good for pulmonary diseases, especially tuberculosis (a common Victorian complaint).

John Cook was anxious to start up business in Egypt and he began to court the British authorities, as well as members of the Khedival ruling circles and the Turkish governor of Egypt. The rumour that Nile traffic was solely in the hands of David Robinson, another travel organiser, was a challenge to him. He began to pitch for the business himself, finally succeeding in obtaining a five-year contract for a new service between the First and the Second Cataracts south of Aswan.

By 1877, Cook was being challenged by others trying to get into the Nile cruise business, including his old rival, Henry Gaze, who had been running Holy Land tours before Thomas Cook’s time. Cook tried to resist the competition, arguing that the Nile was becoming overcrowded, that there was not enough coordination of the services … any number of excuses so that he could monopolise the business himself.

He managed to obtain a contract for control of running of the Khedive’s steamers on the Nile. Nile tourist traffic increased and soon, defects in the services became apparent. The steamers had fulfilled the demands of modest local traffic, but such matters as punctuality, navigational skill, cleanliness and reliability were of relatively little importance. So long as there was some sort of a service, most people were patient and tolerant about the facilities. With the arrival of tourists visiting for limited periods of time and not prepared to rough it, the demand for higher standards of comfort and improved facilities became apparent.

Cook realised the importance of catering to these travellers. He saw that clients in Egypt were, for the most part, of the same level of society as those who had been travelling on Thomas Cooks’s tours to France, Switzerland and Italy since 1855. They were the new middle class and if he wanted to attract them to Egypt, he would have to provide them with something that was not too far removed from their own home comforts.

British travellers to Upper Egypt

The Khedivial Nile steamers, for which John Mason Cook had been granted a concession, were revamped. An atmosphere was created that was somewhat like a up-market hotel. Cabins were furnished with beds and bed linen from England, imported bathroom fittings were installed, separate toilets were provided for men and women and much of the food that could be transported safely in tins was brought from England. The cabin crew was upgraded; waiters dressed in spotless white galabeyas and were made to wear white gloves while serving food.

Cook’s clients proved extremely demanding. They expected their every wish to be met while they, for their part, did not always honour their booking commitments. They complained about the food, about the saddles on the excursion donkeys and about the way the donkeys were beaten. It is an indication of the high esteem in which they held John Mason that they thought he could set right every small thing they did not approve of.

And, in fact, he did manage to achieve most things. At a time when there were no suitable hotels in Luxor, he arranged tent parties in the desert in such a way that they were, to all intents and purposes, on the scale of the most lavish five-star hotels, complete with folk dancing and dancing horses. He made adventure travel a luxury — and the clients kept rolling in.

John Mason had to cope with problems relevant to the times that do not confront today’s tour operator. A matter that constantly concerned him was how to prevent the vandalism of the ancient monuments. In Cook’s day, there was no antiquities law to control illicit digging and the chipping off of pieces from wall paintings and architectural decorations. Tourists were excited when they were aided by local inhabitants who chipped souvenirs off walls of monuments in the hope of gaining bakshish (tip). This only served to increase the vandalism that would continue almost unabated into the 1930s.

When Cook renewed his contract with the khedive and obtained control of the mail-service from Assiut to Aswan, followed by a 10-year contract, he was encouraged to build a fleet of modern steamers. The vessels were built during the 1880s, largely in Britain, and transported in pieces to Egypt, where they were reassembled at a shipyard built by Cook at Bulaq (then still an important river port of Cairo). By the end of the decade, Cook was the master of Nile traffic. He could offer passenger and mail services, a fleet of luxury vessels and accommodation that would satisfy the most discriminating of Europe’s distinguished citizens.

The route trekked by steamers between Luxor and Aswan

Soon there were 40 vessels plying the river Nile, including four large, luxury paddle steamers: Ramses, Prince Abbas, Prince Mohamed Ali and Tewfik. All had private cabins with portholes looking out on the river, wash basins, and some even had a small fireplace for the cooler nights of January and February. A large dinning room served food prepared by a European chef and there was a lounge with comfortable chairs and a library with the latest magazines and board games. The public rooms had fan-cooling systems.

In those days, a voyage in one of Cook’s luxury vessels took 23 days and cost 50 pounds sterling, including shore excursions, the hire of donkeys and guides. Smaller vessels, like Anubis, Cheops, Delta, Isis and Horus, were of the same standard. For the less well-to-do, it was possible to travel on the lower decks of the cruisers, where there was a second-class dining saloon.

The dahabiyas, the quaint paddle steamers, were perhaps the most romantic form of river travel and it was refined to an art. Thomas Cook was at first reluctant to use such an outdated form of transportation, but he quickly realised the potential market for people who did not wish to join the type of tourists attracted to the big steamers. John Cook eventually took over some of the dahabiyas and improved their amenities, adapting the vessels to be driven by a steam engine. They proved to be a booming success, ideal for private parties and for those who wished to travel where they would; not on a regular itinerary, but choosing places to stop as they went along. Arranging their own travel plans, increasing numbers of tourists were happy to organise a holiday in the style of a land-based house party.

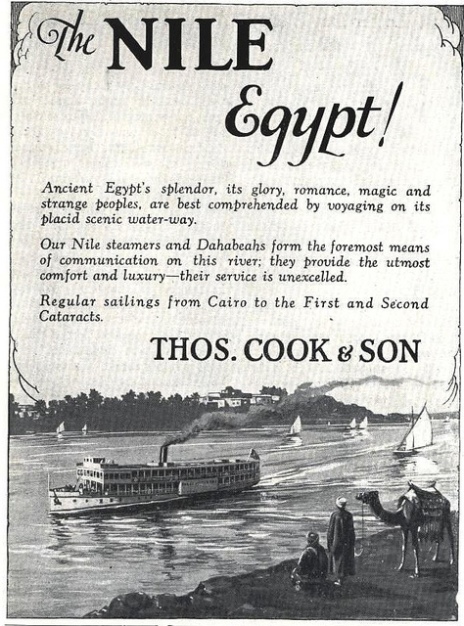

An advertisement by Thomas Cook for the Nile trips

This was by no means cheap travel. Among those who used the dahabeyah were the nobility of Europe, including the Crown Prince and Princess of Sweden, Viscount Wolseley, General Gordon, Lord Randolph Churchill and many others whose names were recorded by John Mason Cook in his leather-bound Nile guidebooks.

Interestingly enough, the itineraries followed by Nile cruises today remain essentially along the lines of those established at the turn of the 20th century. Travel agents have been hard-pressed to improve on the near perfect. Today vessels sail only between Luxor and Aswan, (no longer on the Cairo to Aswan stretch); donkeys have been replaced by luxury coaches for onshore tours; visits to monuments are coupled with visits to bazaars; but the experience is little changed. Perhaps one thing that has regrettably been lost is a certain intimacy impossible to foster in the air-conditioned comfort of today’s immense floating hotels; a familiarity that early tourists must have found so delightful in the tastefully-furnished smaller vessels.

Major world events have adversely affected the tourist industry and with each upheaval, it changes. World War I, for example, naturally put a damper on the business. Things did not really pick up again until the discovery of Tutankhamoun’s tomb in 1922. By that time the land of the Nile had become a cult theme for novels, fashion houses and even cinema, then the newest form of entertainment. Each, in its way, helped promote tourism and brought a different breed of tourists.

Then came World War II, and after that a less discriminating kind of tourist; people who sought culture at the expense of comfort. Today is a time of mass tourism; larger groups of people are coming to Egypt than ever before. They move en masse to places from as far afield as the Mediterranean to Nubia, the Red Sea to Sinai, from Lake Nasser to the Siwa Oasis. But even those who pride themselves on being new-agers — with a new spirit in travel — it is easy to see that it has all been done before. There is nothing new about Nile cruises or adventure travel; desert picnics or donkey rides. Travellers today are following a well-beaten track.

It is true that Cook’s steamers no longer rule the Nile, but they still feature largely on the Egyptian tourist scene. Without doubt, contemporary tour operators are still indebted to John Mason Cook, a pioneer of the Victorian era and the father of all those luxurious cruises between Luxor and Aswan.