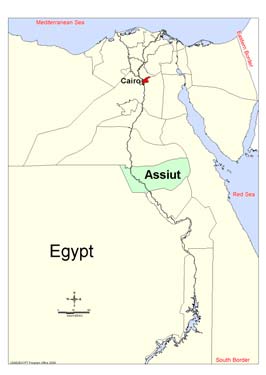

The religious life is always one that is devoted to God, but for those who choose the monastic tradition, it is a life of seclusion. Keeping to themselves is hardly a problem at the remote monastery of Saint Mina Al-Agaiby (the miraculous), on the east bank of the Nile near Assiut, in Upper Egypt, where even the locals cannot give you directions.

You probably heard of the hanging church in Cairo, but have you heard of the suspended monastery? Better known as Deir El-Mualaq (literally, the suspended monastery), the monastery is nestled high up between two massive rocks in the mountain of Abu Foda, roughly 170 metres above ground level.

When we reached the foot of the mountain and I looked up at the monastery virtually hanging in the rock face, I thought for sure we would never reach it. The steep road that leads up to the monastery was not for cars that are weak at heart, and so, like the ancient pilgrims before us, we were forced to make the last part of our trek up to the monastery the old-fashioned way — on foot.

You can see the big contrast between the green fields and the desert from the top of the monastery. Photo: Ayman Ibrahim

Getting to Abu Foda is in itself a trek. The village of El-Maabdna, which lies at the foot of the mountain, is situated on the outskirts of the city of Abnoub, roughly 35 kilometres northeast of Assiut. We had to cross the Nile by ferry and then hire a car to the monastery. Making your way across the Nile in this part of Upper Egypt is a mini-vacation through Egypt’s natural elements: the lush, green agricultural lands, the calm waters of the Nile and the desert beyond.

Once on the east bank of the Nile, we made our way along the narrow road, lined with palm trees, out to Abu Foda. We passed farms and small traditional homes and saw children playing. What we didn’t see were any signs telling us we were even remotely in the right place. There was no indication that Dier Al-Mualaq was in our midst, much less a scrap of an arrow pointing “this way.”

But I’ll say it now: the trip is worth it. From the monastery the view is breathtaking, and the ascent up the stairway that leads to the monastery is one you will probably make alone. We spotted the ruins of a small village, believed to be a Coptic community from the fifth century A.D. while making our way up to the ancient keep (tower).

Partly built of brick and partly rock-hewn, the keep is divided into three floors, the first mainly populated with cells for the monks. The second floor consists of three rooms used as a sacrificial hall in honour of the saint. The third floor leads to the top of the keep, where the two churches of the monastery are located, both carved into the rock.

The Church of Saint Mina is a modest place of worship, built into an ancient cave. No rich rugs, icons or chandeliers here; its significance is its age and location. The wooden gate of the presbytery bears Coptic inscriptions like those on the gates of El-Suryani (the so-called Monastery of the Syrians) at Wadi Al-Natrun. One of the monks accompanying me explained that the Arabic and Coptic inscriptions on the gate were the names of people who had financed some restorations inside the monastery some 300 years ago. The monastery’s other church was converted from a Pharaonic temple. Today it is the Church of the Virgin Mary and Archangel Michael, but the ancient shrine is still evident in the Pharaonic inscriptions that remain.

The wooden gate of the presbytery bears Coptic inscriptions like those on the gates of El-Suryani.

Photo: Ayman Ibrahim

According to Bishop Lukas of Abnoub, the monastery is typical of the hermitages around Assiut from the fourth century, when monks used to live in different places, without a uniform style. “For example, Saint Yohanna El-Assiuti lived in a two-room cell with a window, through which he could see those who came to visit him,” Bishop Lukas explained. “Other monks lived in small monastic communities. Still others lived alone in caves, either at the edge of the agricultural land, or deep in the desert.”

At the time, the Nile attracted many monastic groups; echoing earlier Pharaonic traditions of making offerings and prayers to the river to ensure a good crop. “Some monks took on the responsibility of praying for a good flood,” Bishop Lukas said. “Saint Yohanna El-Assiuti had the reputation of knowing the unknown, and was able to predict the rise and fall of the flood, as well as anticipate the crops. For that reason, during the annual celebrations performed at the beginning of the flood season, he was asked to bless the water of the Nile instead of the pagan priest.”

The monastery itself has been renovated, with two new buildings constructed beside the ancient keep. One houses an icon of Saint Mina Al-Agaibi, the other is used as a storeroom for incense, candles, oil and flour for the sacred bread. New cells for monks were also set up, as well as a new receiving hall for visitors. I asked around to find out if the monastery had a steady flow of visitors, but it seems that it is mainly a place of pilgrimage for Egyptians, who tend to come in big numbers during the annual mulid, which takes place from 8 July to 8 August. Foreigners are few and far between.

But it is obvious that one need not be a Copt to appreciate both the beauty and serenity of Deir El-Mualaq. I wondered whether the monastery could develop into a tourist destination — and whether the monks would in fact want to play host to backpackers and holy route tourists veering off their itinerary. For now, Deir El-Mualaq is best left as it is.